Written by Manon Salé

Introduction

This adventure began in 2018. At the time, I was in my 3rd year at the Institute of Politic Studies in Rennes, France, studying sustainable development and political science. The school required students to go abroad for at least 6 months, either on a university exchange or as an intern.

I chose the second option: I wanted to find out about the world of work, and it gave me more flexibility in choosing the country I wanted to go to. As the master’s degree I was aiming for was focused on Nordic countries, I started looking for a work placement in that part of Europe. A friend of mine, who had just returned from Sweden, advised me to apply to the organisation where he was working: Sustainable Sweden Association, that helps local authorities and businesses to adopt more sustainable ways of doing things, inspired by the ecomunicipality model. I took his advice and was accepted. So, I went to live in Umeå for 6 months and met Torbjörn Lahti, President of Sustainable Sweden Association.

Torbjörn hails from the Torne Valley, a very special part of Sweden, home to one of the country’s 5 minorities. More specifically, he was born in the municipality of Övertorneå, Sweden’s very first ecomunicipality. He was one of the key people behind the project.

Once my internship was over, I kept in touch with Sustainable Sweden Association and Torbjörn Lahti. I continued to work with them on some projects, including the Ecomuna project. Its aim is to build an international online capacity centre to train municipalities around the world to understand and adopt the principles of ecomunicipality.

It was as part of this collaboration that Torbjörn asked me to come back to Sweden, 5 years later. This year, Övertorneå is celebrating its 40th anniversary as an eco-municipality. It seemed important for Sustainable Sweden Association to mark the occasion by proposing a special way of celebrating this anniversary: to produce an on-the-spot report highlighting the work carried out in Övertorneå.

This report has a very specific objective: to understand why this municipality became Sweden’s very first eco-municipality. What made the project work here?

For Torbjörn, one of the reasons was Övertorneå’s ‘soul’. So I went to Sweden with this very mission: to find the ‘soul’ of Övertorneå. And I think I’ve managed to catch a glimpse of it.

I should point out that this is the work of an outsider from another country, France. This outside perspective allows me to see some local particularities of which the inhabitants may not be aware, but it also limits my understanding of the area. So I don’t claim to have found the truth: this is my personal experience, over a one-week period.

A huge thanks to Torbjörn Lahti and the town of Övertorneå for giving me the opportunity to make this trip. Thanks to Christina Snell-Lumio and her family for their hospitality and for allowing me to meet the people who make up the ‘soul’ of Övertorneå. Many thanks to Ann-Britt and Ahti Aasa, Marita Mattson Barsk, Per Huuva, Victoria Luttu, Annika Keisu Lampinen, Ulf Hannu, Bengt Aili, Auli Andersson, Margot Husson and Kurt A. Larsson for agreeing to meet me and give me an insight into life here. Finally, thanks to Mona Lahti and John Wear for their friendship.

Övertorneå, the first Ecomunicipality

Övertorneå is a municipality in northern Sweden, in Norrbotten county, on the Finnish border, along the Torne river. It covers an area of around 2,374 km² and has a population of over 4,200, with a density of around 1.8 inhabitants per km². Its administrative and political centre is in the village of the same name, Övertorneå, which has just over 1,700 inhabitants.

The birth of the project

In the 1980s, the municipality was suffering from a severe economic crisis, coupled with a rural exodus: its inhabitants were moving to bigger cities in search of work and better living conditions. In his book My journey with the Ecomunicipalities, Torbjörn Lahti explains that “The population had decreased by 40% since the 1950s, and it was primarily young people that moved”. This led to a high level of pessimism among the population, who were living in an area with a poor image.

To remedy this, the then mayor, Kurt A. Larsson, and his team decided in 1983 to launch a programme called “Study of the Future”, based on three pillars: economy and labour, social welfare and culture. The aims of the study were to revitalise the municipality, to make it attractive again and give meaning to the people who lived there. That same year, the municipal team had the opportunity to visit a Finnish municipality, Suomussalmi, which had given itself the title of ecomunicipality. Inspired by this visit, the elected representatives decided to make Övertorneå an ecomunicipality, the first in Sweden. They hired Torbjörn Lahti to bring the project to fruition. The method chosen to implement this concept was based on discussion and collaboration with citizens. The aim was to put in place a model that would help citizens to take their future into their own hands, while addressing both economic and ecological issues. Kurt A. Larsson, whom I met, explains it this way: “The municipality started to visit all the villages and talked with the people. We had study groups everywhere, about what activities people wanted to do. And it was a success: people here were positive about the project.”

Kurt A. Larson

The time for success

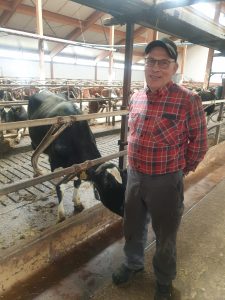

The ecomunicipality project initially focused on the issue of agriculture. Since 1984, the local authority has been working with residents to launch a number of alternative, environmentally-friendly farming projects. A local partnership was set up with the distributor Konsum Norrbotten, which undertook to sell the produce in supermarkets. Some plantations have been able to obtain KRAV certification, which guarantees the organic origin of the vegetables. “At that time, there were organic farmers in almost every village,” recalls Ulf Hannu, a local cow farmer. “It was small farming, no big companies.”

In the next few years, the project became institutionalised. In particular, this led to the creation of Ekotopen, a foundation formed with the help of Luleå University of Technology, whose aim was to give a deeper dimension to the Ecomunicipality project.

In 1992, the Övertorneå project was presented by the Swedish government at the Rio Conference. The government emphasised “the importance of vision and the power of example” in bringing transition projects to fruition.

In the years that followed, the actions carried out as part of the Eco-municipality project diversified: waste management, allergy prevention, awareness-raising in schools, ecological construction, green energy production (windmill, solar panel), sustainable transport in the municipality and many others.

Ulf Hannu

Övertorneå : a model for the rest of Sweden (and abroad)

That said, the ecomunicipality project did have a positive impact on the area, which continues to this day. In particular, it has helped to raise the profile of local culture, a culture that was previously depreciated. Moreover, Övertorneå is still a source of inspiration for other areas wishing to make a sustainable transition. This is reflected in the spread of the concept in Sweden, where there are more than a hundred ecomunicipalities. Several other countries have also shown an interest in this model, including Japan, the USA and Ethiopia. So the project set up in Övertorneå 40 years ago has convinced many other local authorities, both nationally and internationally.

Margot Husson, one of Torbjörn Lahti’s past interns, who came to the municipality a few years ago, was very inspired by this international aspect. She told me : “I was quite struck by the international dimension of Övertorneå. The municipality has seen delegations from Japan, Chile, etc. who have come to be inspired by what is being done here. Övertorneå’s link with the rest of the world is quite strong, particularly as it is located at the Arctic Circle and is bearing the full brunt of the effects of climate change. The inhabitants here are aware of their link with the world”.

But why did this project worked here in the first place ? Why did Overtornea became the first ecomunicipality ? In order to answer that question, we need to take a look back in history.

Victoria Luttu

A (short) history of the local culture : the Meikäläiset people

Övertorneå is a municipality located in a very special area, along the Torne valley, which separates Sweden and Finland. Its population is descended from people who settled here long before Sweden became what it is today : the Meikäläiset. They are one of the country’s 5 national minorities: the Tornedalians. These people have their own traditions and culture, some of which overlap with that of the Sami. Historically, the Tornedalians lived a lifestyle very close to nature : reindeer herding, hunting and fishing. Above all, they have their own language, Meänkieli (which means “our language”), derived from Finnish.

A peaceful territory

Originally, the Tornedalians considered themselves to be a single people, regardless of which side of the river they were on (Finland or Sweden). They shared a common way of life, a common language and intermarried. Even today, some of the villages on either side of the Torne river share the same name.

The very first kingdom of Sweden was born in the middle of the 6th century in the south of the country, with Uppsala as its political and religious capital. It was then made up of autonomous provinces. Until 1523, when the modern Kingdom of Sweden was founded, the country’s history was punctuated by internal family wars for power, as well as conflicts with neighbouring kingdoms.

This long period had little impact on the people of the Torne valley: Sweden’s ambitions and challenges lay mainly in the south of the country, and successive rulers showed little interest in the peoples of the north. This is what Marita Mattson Barsk, a specialist in local history, explained to me: “at that time, we used to live in peace here, with connections to Russians, Norwegians or Finnish people, without really caring about what was happening in southern Sweden”.

Marita Mattson Barsk

The Torne Valley : a “threat” to the national identity of Sweden

After 1523, however, the Kingdom of Sweden began to turn its attention to the riches of its northern lands: “The king started to be interested in our water, our iron, our wood. So he built roads to get there”. The creation of roads encouraged the development of trade between the Tornedalians and the rest of the kingdom, as well as the Christianisation of the valley, as more and more religious people entered the villages (the Church had become Lutheran in Sweden by this time). This represented a first break for the local populations, who were more or less forced to come into contact with the rest of the kingdom.

But the date that really marked a turning point for the Tornedalians was the annexation of Finland by Russia in 1809. Indeed, Finland had been under Swedish control since the 13th century. However, at the end of the 15th century, Russia began to show an interest in Finnish lands. There followed a series of wars and truces to conquer the territory, which were eventually won by Russia. Faced with this threat, the Kingdom of Sweden decided to forcibly unify its territory and its peoples. It paid particular attention to the Tornedalians because they had remained close to Finland: they spoke a language derived from Finnish, Meänkieli, and still interacted with people on the other side of the border. For the Kingdom of Sweden, this represented a threat to the unity of the country. It was therefore decided to make the Tornedalians “true” Swedes: the Swedish language was imposed on them, whether through the schools or the Church, and they were forced to abandon their local cultures and traditions.

This period still represents a certain trauma for the Tornedalians. “People here no longer had an identity,” explained Ahti Aasa, who works at a local radio station that broadcasts only in Meänkieli. “Our language and traditions had been taken away from us. People were ashamed of their own culture. Many felt crushed and humiliated. You can still see the marks of that era on Tornedalians: not everyone is proud to come from here. Parents don’t teach their children Meänkieli. We’ve lost out in terms of knowledge and transmission”. This acculturation of the Tornedalians lasted until quite late, as Marita Mattson Barsk told me: “The work against the local language was very strong between the 30s and the 40s. Local libraries were not allowed to buy books in Finnish until 1957. People here had to go to the Finnish side of the river if they wanted to read Finnish.” Like Ahti Aasa, she sees the negative impact of this policy on local culture: “Meänkieli nowadays is mainly a talk language. Writing is difficult, mainly because it was forbidden to read and write it for many years”.

Toward a reappropriation of local culture

However, local culture is enjoying a revival. Since 2000, Meänkieli has been recognised as an official language of Sweden, making Tornedalians one of the country’s five national minorities (along with Sami, Jewish, Rom and Finnish). This recognition was followed by the Swedish government’s efforts to promote local culture. Today, Meänkieli is spoken by between 40,000 and 60,000 people. There are 3 forms: the main one, in Övertorneå (Matarengi en meänkieli) and two others further north, around the iron mines. A Meänkieli study centre, the Övertorneå Culture and Research Center for North Calotte, has also been set up in the heart of Övertorneå to bring together all the literature available about the area. I think I can safely say that the people I met during my stay were proud of their cultural heritage, proud of their identity. “The interest for local culture is back”, Marita Mattson Barsk told me. “I can see it in my own family: my children do not speak Meänkieli but my grandchildren are learning it”.

Local culture is undoubtedly one of the main components of Övertorneå’s “soul”. Despite Sweden’s efforts to smooth out the identity of the Tornedalians, many parts of this culture are still present in the villages today.

A specific way of living together

During my trip to Övertorneå, I was struck by the way people lived together. Back home, in my town, we don’t really care about our neighbours. We pass each other, we greet each other politely, we exchange a few words, but the general feeling is indifference.

Kindness and hospitality

In Övertorneå, on the other hand, living together is at the heart of relations between inhabitants. People tend to help each other and to look out for each other. This has led to the development of a certain informal economy, in which relationships are based on mutual aid rather than financial exchange. You help me today, I’ll help you tomorrow. This framework for living together seems to be very important to the people I met. It manifests itself into strong values of hospitality, sharing and kindness.

Here are two examples:

- When I arrived in Övertorneå, I met Ann-Britt and Ahti Aasa, a couple living in the village of Juoksengi. They told me that, for their daughter’s wedding, many people in the village had helped to organise the event by providing accommodation for the guests, lending crockery and furniture, and so on.

- Later in my stay, I spent a whole day with Bengt Aili, a local resident. He took me to various places that are important to the local culture, so he wasn’t at home all day. As we were driving along, one of his neighbours, who was worried about not seeing him, called to see if everything was OK.

This way of living together can be explained in several ways. Firstly, demographics: the area is sparsely populated, so it’s easier to get to know the people who live and work around you than it is in big cities. But the main explanation, in my opinion, lies in the cultural heritage enjoyed by the Tornedalians. Traditionally, the people of Torne Valley are renowned for their kindness and hospitality. But in a hostile environment, as can be the case in winter, it’s essential for survival to get on well with the people around you and be prepared to help each other out if need be. Annika Keisu Lampinen, a former politician in Övertorneå, explains it: “Before then, there were no roads and anything. So when people made a long way, it was normal to serve them food and beverage. And hospitality became a tradition.” Bengt Aili also agrees: ”Hospitality and good relationships between people are necessary for survival here. You have to get on well with your neighbours because you have to be able to rely on each other, especially in winter.”

Today, this is reflected in the way the people of Övertorneå live together. I myself was particularly welcomed by the people I met, who made it a point of honour to make me feel at ease, with great success.

Annika Keisu Lampinen

Learning to live together from school: the example of Juoksengi’s school

From 1988 to 2007, Ahti Aasa was a teacher at Juoksengi School, which has since closed. For several decades (1981-2007), the school offered its pupils, aged between 7 and 12, a rather unusual way of working, based on autonomy and empowerment. Ahti Aasa explains: “All the things that were done in school could be questioned and readapted depending on the children’s needs. For instance, pupils who needed a physical start of their day asked to do some sport before the lessons so that they can focus more on the lessons. Or there were children who liked to be in school, so they came to school really early even though school started at 8 am. So we had the door open earlier in the morning. Every beginning of the week, teachers and children had some meeting to discuss their goals and activities for the week. Then, at the end of the week, they had another meeting to see if the goals were fulfilled or not. Parents were also involved in the process. It was really successful : children were considered as human beings before as pupils and they were therefore happy to go to school”

This example illustrates the importance of individual autonomy and responsibility at Övertorneå. These two traits are essential for living together, but also for living in a difficult natural environment.

Tornedalians : a passive people ?

During my stay in Övertorneå, several people explained to me that, while the Tornedalians were indeed characterised by their hospitality and kindness, they also sometimes had the reputation of a population that prefers to remain passive when facing some events and changes, in particular to preserve community life. Annika Keisu Lampinen sums it up as follows: “Here, we are no trouble makers. Even if we don’t like something, we say nothing and we stand still. That is why perhaps sometimes we don’t take actions to change things.”

For Marita Mattson Barsk, a local cultural personality, this can be explained by the influence of religion, and more specifically of the Lutheran priest Lars Levi Laestadius, who had a lasting influence on the region in the 19th century. Indeed, Laestadius preached a certain acceptance of events, which is still prevalent today: “We have a philosophy here that whatever happens, you have to deal with it. It can be seen as a passive behaviour but it can also be seen as a strength and as a type of resilience”.

A specific way of living with nature

In the last article, I was explaining how Övertorneå people were living together. Besides this very specific way of living together, the Tornedalians also have a specific way of living with nature.

When you arrive in Övertorneå, you quickly realise that nature is a strong marker of identity for the people who live there. It is even a marker of identity for the villages themselves, which tend to define themselves by their environment. For example, people living in villages in the forest have a slightly different identity to those located along lakes and rivers or on the banks of the Torne river. Some inhabitants will feel closer to the woods, others to the water.

However, we can say that there is a fairly common way of living with and in nature in the area. This is reflected in the activities of local residents. Here, it’s common to spend time in nature in one’s spare time. Not in a passive contemplative way, but rather in an active way, by taking advantage of natural resources. This might involve fishing, hunting or picking wild berries. Growing your own vegetables is also a widespread activity: most of the people I met had their own vegetable garden. “When I arrived, people asked me when I was going to plant this or that vegetable”, Christina Snell-Lumio, a member of the Ecomunicipality board in Övertorneå, told me. Originally from Lulea, she married a man from Övertorneå and lives in the village of Hedenäset. “It was obvious to them that they had to grow their own vegetables, whereas I hadn’t really thought about it”.

“A win-win relationship”

Living with nature also means contributing to its health, conservation and preservation. It’s about taking care of our environment so that we can make the most of our resources (wood, fish, meat, berries) without exhausting them. Bengt Aili, a resident of Övertorneå, explained it to me as follows: “It is a win-win relationship with nature. It’s essential to preserve nature if you want to be able to use natural resources. What I give to nature, it gives back to me. If it leaves me alone, I leave it alone”. For example, Bengt Aili regularly maintains the forest around his home. In certain areas, he cuts back small shrubs to allow other trees to grow better. His vision is shared by Per Huuva, a Sami who lives in a village in the Övertorneå area and is specialised in local cuisine. He told me about local hunting practices, which are designed to respect nature: “When you go hunting, there are certain rules to preserve animal populations. For example, you don’t kill an elk that is expecting a child”. And this approach seems to be bearing fruit: “here, the elk population increases every year”, concludes Per Huuva, despite the importance of hunting in the region.

Just as the local way of living together, this way of living with nature can be explained by the cultural heritage enjoyed by the Tornedalians. Their ancestors traditionally had a special relationship with nature, a relationship of interdependence. For example, historically, it was very important to have access to a waterhole from one’s property, whether it was a lake or a river, in order to benefit from aquatic resources. This is still reflected today in the daily activities of local people and in their conception of their relationship with nature, as we have just seen.

Per Huuva and Bengt Aili

Conclusion

Throughout my stay, I was quite impressed by the people I met and their way of life. I felt inspired by this specific way of living together and with nature. I think I got a glimpse of the ‘soul’ of Övertorneå and I’d love to be able to bring some of that ‘soul’ back into my personal life: more nature, more togetherness.

I was also quite struck by the way Tornedalians view their way of life and culture. I’ve been told many times that “it’s not a big deal”, “it’s just the way things are”, or that “it’s just common sense”. But, having lived in many different places, I can see that it’s not as obvious as all that. There is something special going on here. This is also the opinion of Christina Snell-Lumio, a local politician who was born in Luleå: “People here often say that their way of life isn’t all that special. But it’s only here that I’ve come across this relationship with others and with nature”. Annika Keisu Lampinen, a former politician, agrees: “we in fact do not know that we are as sustainable as we are. A lot of things we do seem natural for us : not using too much hot water, using a bicycle. I realized that when I grow up and I am now very proud of it”.

And it was indeed the local way of life that enabled the ecomunicipality project to be born and to take hold fairly quickly among the residents, back in the 1980s. In fact, the elected representatives who led the project started from the grassroots, from what the population was already doing and what they wanted to do. They drew on the local philosophy of living together and living with nature. According to Annika Keisu Lampinen, this is the strength of the ecomunicipality model: “the ecomunicipality project was successful because it was not something new. It was something people were already doing”. And that explains why this model can easily be transposed to other areas and other contexts: if you start from the ground, you can’t go wrong.

Today, it’s true that Övertorneå continues to lose residents. Young people in particular are leaving to study, to be closer to the city or to discover other places. But I’ll conclude with a quote from Mona Lahti: “Yes, young people are leaving. And that’s important, it allows them to see other things, to discover other ways of life. But the important thing is that they come back with all this new knowledge. Come back with everything you’ve learned”.